By Taryn Assaf

“Korea is Samsung, and Samsung is Korea”. This phrase is commonly heard and almost religiously believed by much of South Korea’s urban population. Much of what outsiders know about South Korea is Samsung, and taken from a purely economic perspective, that’s not so hard to believe: the top 30 Korean corporations make up 82 percent of the country’s exports, with Samsung being the largest. Not so long ago, South Korea was a different world entirely. Rewind to the 1970s and you’d find a population of 50 percent farmers compared to just 6.2 percent today. You’d find an economy sustained by the agricultural, rather than the technology, sector. You’d find a country that was 80 percent food self-sufficient compared to fifty percent in 2012, (however, if we take away rice and grains, the self sufficiency rate drops to a staggering six percent)[i] the lowest among OECD nations. What this has meant for Korean farmers is a total loss of livelihood; what it means for Korean citizens is a near complete reliance on foreign foodstuffs, which, as evidenced by the 2007 global food crisis, can lead to shortages and price hikes, tightening the already stretched average household budget.

Farming in Korea began its decline in the 1980s when the United States began applying pressure on South Korea to dismantle trade barriers that had, until then, protected its domestic agricultural sector. With the threat of trade sanctions, Korea opened its markets to US beef, wine, tobacco and rice. Facing large deficits in trade, and realizing it no longer needed to use its food surpluses to strengthen Cold War alliances, the US argued that agriculture should be incorporated into trade negotiations. The World Trade Organization (WTO) began pressuring the world’s farming sectors to open their markets to global competition. In 1994, Korea entered the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)[ii] with the WTO, welcoming the near demise of its agricultural sector. This forced the government to eliminate quotas and tariffs on agricultural imports from the US and European Union, which both subsidize their farmers and agribusinesses to the combined sum of $1 billion a day. After the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the International Monetary Fund imposed further liberalization policies on Korea’s agricultural sector, hurling Korean small farmers out of competition (and for many, out of business entirely). All of this has resulted in a four-fold debt increase – an average of approximately $30,000 USD – in farming households since 1995, which continues to rise. What only forty years ago was a thriving industry is no longer a viable way of life, and Koreans must fight to hold on to their right to farm and their right to food.

As a result of bad industry and agricultural policies, food is treated as a commodity rather than a human right. The right to

healthy and culturally appropriate food produced sustainably and according to a people’s own agricultural system – a concept otherwise known as food sovereignty – is continually undermined by structural barriers caused by market demands, corporations and complicit governments. Therefore, prioritizing the needs and livelihoods of food producers, distributors and consumers is central to a sovereign food system. Korea’s peasant farming population has been a world leader in reclaiming that system. In October 2012, the Korean Women Peasants Association (KWPA) was awarded the Food Sovereignty Prize (FSP) by the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance. The FSP was developed as an alternative to the more famously known World Food Prize.[iii] It celebrates small farmers and other food producers who use socially just, environmentally sustainable and economically viable production systems. The KWPA coordinates and carries out a number of activities throughout Korea designed to empower women through the process of sustainable farming.

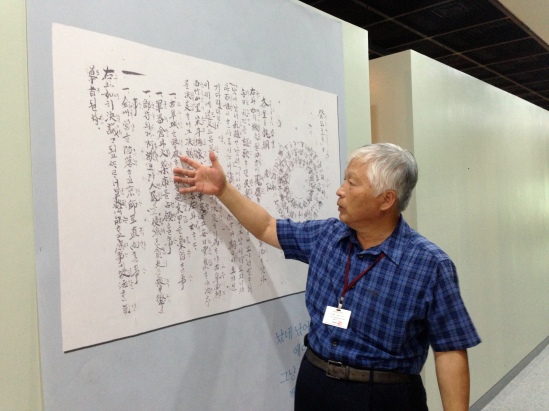

One of KWPA’s main initiatives is empowering women peasants through indigenous seed preservation. Indigenous seed preservation was traditionally the responsibility of women as a consequence of the conventional division of labor on the farm. According to Hyo-Jeong Kim in her conference paper, “Food Sovereignty: A critical Diologue”, “the seed economy was a women’s economy”. During Korea’s Green Revolution in the 1970s, government policies that promoted and favored industrial farming led to the loss of women’s indigenous skill and knowledge. The practice of seed preservation became nearly extinct as industrial farming methods became the norm (buying seeds, fertilizer and soil; using heavy machinery, and increasing crop yields). Not only was this a loss of expertise, it was a loss of women’s empowerment. Native seeds and their crops embody the knowledge and skills of women peasant farmers, so to disregard that knowledge is to erase a large element of women’s agency on the farm. Despite the erasure of seed preservation from modern agriculture, many women held on to the practice. To sustain KWPA’s initiative, therefore, requires that that knowledge be passed down from the now elderly women peasant population to the younger farming generation, which is only familiar with industrial farming methods. Making seed preservation once more a priority in agriculture means making women’s knowledge and instinct a priority; it means transferring power from seed manufacturing companies back to women.

Sister’s Garden Plot (SGP), for instance, aims to connect consumers to women food producers who collectively grow and deliver weekly, biweekly and monthly packages of organic produce and other homemade products to consumers’ doorsteps. They also sell organic sesame oil and soy sauce, among other a-la-carte items, on their website. SGP currently operates 26 farm communities throughout Korea. The program aims to create a solution to the crises caused by neoliberalism and a globalized food production system. From their website, “SGP believes in sustainable, organic farming, in protecting and preserving biodiversity, in safeguarding native seeds, and in realizing peasants’ rights.” In doing so, they are reclaiming their right to a food production system that puts power back in the hands of producers and consumers. Also from their website, “As a result of their efforts, women peasants in these communities take pride as women peasants and have achieved greater social recognition in their homes and villages”.

Sister’s Garden Plot (SGP), for instance, aims to connect consumers to women food producers who collectively grow and deliver weekly, biweekly and monthly packages of organic produce and other homemade products to consumers’ doorsteps. They also sell organic sesame oil and soy sauce, among other a-la-carte items, on their website. SGP currently operates 26 farm communities throughout Korea. The program aims to create a solution to the crises caused by neoliberalism and a globalized food production system. From their website, “SGP believes in sustainable, organic farming, in protecting and preserving biodiversity, in safeguarding native seeds, and in realizing peasants’ rights.” In doing so, they are reclaiming their right to a food production system that puts power back in the hands of producers and consumers. Also from their website, “As a result of their efforts, women peasants in these communities take pride as women peasants and have achieved greater social recognition in their homes and villages”.

KWPA is not the only, nor the first, organization in Korea leading the alternative agriculture movement. Hansalim began in 1986 as Korea’s first agricultural cooperative and is now the largest such cooperative in the world, boasting close to 400,000 household memberships and 2000 food producers. They believe in a healthy exchange between rural producers and urban consumers through the purchase of products and through tours, cooperation activities, education programs and campaigns. To build trust between consumers and producers, Hansalim offers an “Autonomous Check System” whereby consumers and producers can go through the production process together. This is meant to ensure transparency and quality, thus developing relationships with farmers and their products.

Hansalim offers a wide variety of products, ranging from living and household items to fresh produce to processed foods (seasonings, snacks, and side dishes). To protect food sovereignty, they support all domestic producers, not only those who use organic methods (some use low levels of pesticides, although priority is given to organic producers) and focuses solely  on local items. Livestock producers, for instance, use domestically grown barley to feed their livestock, bypassing the need to rely on grain imports and securing 400 hectares of barley producing land. Additionally, each product comes with a label detailing the number of kilometers traveled and the amount of carbon emissions saved in comparison to a similar imported product. The focus on local allows members to experiment with seasonal products and re-acquaint themselves with the traditional food culture.

on local items. Livestock producers, for instance, use domestically grown barley to feed their livestock, bypassing the need to rely on grain imports and securing 400 hectares of barley producing land. Additionally, each product comes with a label detailing the number of kilometers traveled and the amount of carbon emissions saved in comparison to a similar imported product. The focus on local allows members to experiment with seasonal products and re-acquaint themselves with the traditional food culture.

To make shopping easy and convenient for its busy, urban customers, Hansalim offers home delivery options in addition to its 154 stores across the country. They even offer an app for iPhone and Android, through which users can access seasonal food information and Hansalim news, among other features.

Re-building Korea into a food sovereign nation is, by no means, easy. Cooperatives like Hansalim and organizations like the Korean Women Peasants Association embody the true meaning of food sovereignty, where priority is given to local production for local markets, based on local knowledge and resources. Many CSAs have sprouted up in response to the success of others – Gachi CSA (formerly WWOOF CSA), for instance, targets English speakers in Korea. Movements like these re-prioritize the lost relationship between consumers and producers in ways that ensure a dignified income for the farmers whose livelihoods have been eaten into by free trade and neoliberalism. They stand up for marginalized groups and stand against the environmentally degrading practices of large-scale industrial farming. Peasant farmers in Korea are nurturing the crops of sustainable agriculture with love and care, and are reclaiming a food system they can truly call their own.

[i] Anders Riel Mueller, The Fight for Real Food in Korea, Korean Quarterly, Winter 2012

[ii] The AoA is “the economic engine for promoting industrial agriculture — replacing family farmers with agribusiness, family farms with corporate farms, and biodiversity with monocropping.” Anuradha Mittal, Losing the Farm: How Corporate Globalization Pushes Millions off Land and Into Desperation; The Multinational Monitor, July/August 2003, 24(7/8)

[iii] The World Food Prize celebrates increased agricultural production through the use of industrial agriculture. Its recipients have included Monsanto’s Executive Vice President, Robert Fraley, for work developing GMO crops used in the U.S. Critics of the WFP state that it champions pro-GMO corporate agribusiness and the corporate owned global food system.