labor

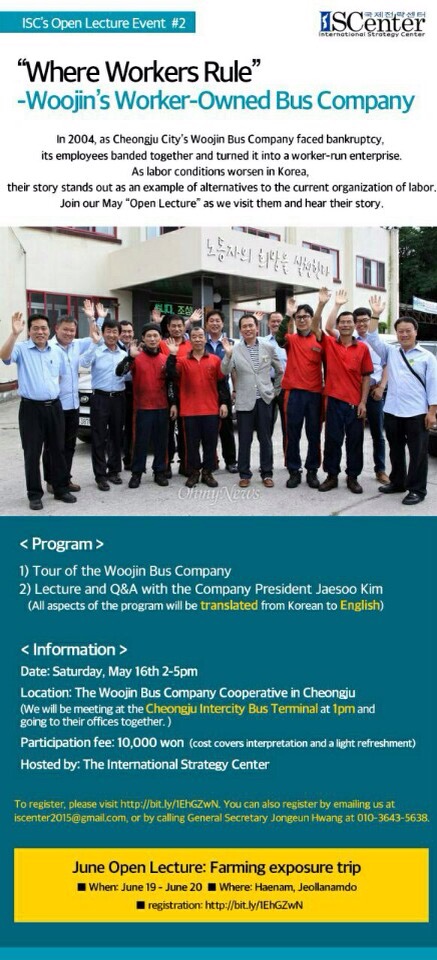

Taking Down Samsung’s No Union Policy: The Samsung Electronics Service Union

On July 29th, The International Strategy Center’s Policy and Research Coordinator Dae-Han Song and Communications Coordinator Hwang Jeong Eun met with Sunyoung Kim, the chair of the Samsung Electronic Service Union for the Yeongdeungpo District in Seoul of the Korean Metal Workers Union to talk about the union’s struggle and their trailblazing as the first union recognized by Samsung.

Can you give us a brief background to the Samsung Electronic Service Union?

We started the union because of the harsh working conditions. Sometimes, we might work 12 to 13 hours a day, and still not make the minimum wage. You might come to work on Saturday or Sunday from 8 to 6 PM and come out on the minus. Why? Because you didn’t get paid, but you still had to pay for lunch and gas. You even had to pay for your own training from Samsung. In addition, our work is dangerous, whether it is installing air-conditioning, or climbing a wall, or working with live electricity. Despite these dangers, the company doesn’t provide any safety equipment. We have to wear neckties even when working with moving parts. They force us to wear dress shoes even when working on a roof in the rain. Why? For the sake of maintaining a clean and professional image.

How can a person work 12 to 13 hours a day and not even get paid the minimum wage?

It’s a system based on commission. There is no base pay. You are basically a freelancer. You come in to work, and if there is work you work if there is not then you just stay in the office. However, while a real freelancer can decide whether or not to show up to the office, we have a specified clock in and clock out time. When there is work, we just keep working. In the summer, there’s a lot of work: air conditioning, refrigerators. So, we just keep on working until everything is done. Not only is working such long hours exhausting, it is also exhausting doing so in the summer heat. Sometimes you don’t get home until 12 AM and can’t even rest on the weekends. That’s when we make our money that carry us through the fall, winter, spring when there is little work. In these off seasons we might sometimes just get one or two calls in a day and since we get paid by commission, if we don’t work, we don’t get paid.

You have to at least pull off 5 or 6 jobs a day to make 1.5 million (about $1,500) a month. And that doesn’t include gas, your tools, your training which you have to pay out of pocket. I’ve worked at Samsung Electronics Service for about 15 years. So, in some ways, I am part of the upper echelons of the workers. I made 50 to 60 million won a year on average. So, the pay was enough. I worked hard and worked until late. I also accumulated a lot of know-how and developed relationships with customers. But, I was part of the minority, maybe I fell within the 15 percent of highly skilled and experienced workers. The rest, they are not in the middle, they are all at the bottom. There is no middle in this system. There are those that make a lot and those that don’t make enough. Those on the lower levels make about 20 million a year. That’s why the conditions are so poor.

The commission system pits us against each other. If I finish my work just a little faster, then I can finish two instead of one. The majority don’t have enough steady work. There’s not much one can do, other then parcel out one or two of my assignments to them. The company is unwilling to take responsibility for these workers.

When you are organizing a union, you have to build worker solidarity, but the system itself creates competition among the workers. Did that make it difficult to organize?

If we look at our system, we can see that it breeds selfishness. In the Yeongdeungpo branch, we originally organized 80 workers. But, it collapsed and only 24 members remain. The owner of the service branch planted the seeds of doubt: “Do you really think you can beat Samsung?” “Just do your work properly.” “I’ll give you more work if you quit the union.” “I’ll give you less work if you don’t.” So, 70% of the union members dropped out. When Choi Jong Beom killed himself, it had a huge impact on us. Before, we were just a Kakaotalk (a smartphone messaging application) union, but after his death those of us that remained began to meet in Seoul. So, while there weren’t many of us left, our union grew stronger. While we might be a fraction of what we were in the beginning, we are stronger now than before.

What are your demands?

At first we were demanding that we be made into Samsung regular workers. Samsung was directing us, training us, so it just made sense that we would be working directly under them. Now our demands are just improved working conditions. Being an engineer, fixing things with my hands, was my childhood dream. But, the company only cares about using us to make money. We want Samsung to appreciate and nurture our skills. That means paying us decently. We are asking for a basic wage in addition to the commission. Ultimately, we want to move towards a fixed monthly wage. Workers get stressed not knowing how much they will make in a particular month. Also, we want people’s skill and experience to be acknowledged. Right now, there is no difference given between a one year or a twenty year worker. They are treated as the same. After the collective bargaining, about 50% of our problems have been solved.

Where is the struggle right now?

When we went back to our service centers after concluding an agreement, the owners of the service centers say they will not recognize the union. They refuse to honor it. Under the agreement, if workers bring their receipts for gas, cell phone usage, for their meals, then the owner needs to reimburse them. The owners refuse to recognize this and just say, “We paid for it already. I’m going to keep paying you as I did before.” So, we are struggling against the branch owners. But ultimately, this isn’t about the branch owners, it’s about Samsung who is directing them.

What’s next?

So right now we have about 1,600 Samsung Electronics Service union members. Previously, we had about 6,000. Many left because they are afraid of what the company will do to them. So our focus will be to organize them. It hasn’t yet sunk in, but people around us tell us we should be proud that we, subcontracted workers, broke Samsung’s 76 year union-free history. I think it is these people that stood in solidarity with us that played a huge part in our victory. Many of them are more experienced union organizers, and we are a new union, so these seniors give us guidance on where we should go, how we should organize workers and the non-unionized centers. On August, we are going to organize the non-unionized centers.

Have things improved?

So according to the collective bargain agreement, the company needs to follow the labor laws. That means that if we work over 40 hours a week, we should get overtime. We are supposed to get paid holidays. And as I mentioned before, the company should refund 100% of the costs of gas, parking, equipment, cell phone, and leased cars. We also won a basic 1.2 million won a month wage. But, the best thing is that the owner can’t unilaterally change work policy: he has to negotiate with the union. They can’t just take us for granted. I mean all this should just be the given.

So what’s still missing?

The first thing is that we don’t yet have a 100% fixed wage. The second one is that the collective bargaining agreement contains vague and difficult to understand wording. We are an inexperienced union and because we rushed the negotiations, there is a lot in the contract that is vague and up for interpretation. That’s what we were struggling for in the 40 day occupation at Seocho and what we are fighting for at the branch level now: a more clear collective bargaining agreement.

How can people in Korea or abroad help?

I learned that there are 10 million irregular workers. In the case of Samsung and LG, they are a world class corporation, but in their pursuit of profit they outsource and sub-contract. This wouldn’t be a problem if they paid decent wages and created a stable system. But that’s not the reality. Companies like Samsung are shiny and nice on the outside, but the inside is different. When I tell people about the working conditions that I face, they ask me, “Are you telling me that there are still companies like that?” I want to tell the world about the conditions we face working in these corporations so that we can stop them guard our rights. I want to be a dignified worker that can proudly wear the company logo on my shirt.

Now because of our struggle, those that install internet for SK, or LG U+ they are also awakening to the injustice of their situation. They are realizing how similar and unjust their work is which does not guarantee a basic wage. I want to let those in Korea and abroad know our conditions so that we can improve them.

70s Women Workers

by Dae-Han Song

Among the key worker struggles during the Yushin Regime of Park Chung Hee were those waged by women at the Cheonggye, Dongil, and YH Unions. After watching the play 70 Women Workers by the Arts Collective for a New Era, we spent a weekend meeting up with its three protagonists. Our first day, we got a tour of Pyounghwa Market (the primary textile district in Korea) by one of its then-organizers Shin Soon Ae. Our second day, we sat down at a Gwanghwamun café to talk with Lee Cheong Gak and Choi Soon Young presidents of Dongil and YH Union during its most intense and fierceest struggles.

Shin Soon Ae: A Born Again Worker

Walking into Café Myongbo (Treasure) is like walking into the 70s. The walls and upholstery are stained with the past, and its

customers are now aged. Shin Soon Ae, a movement elder and once unionist at Pyounghwa (Peace) Market, suggested the café; Korean labor martyr Jeon Tae Il and his Samdong Friendship Association held their meetings here. It was a hip place where young people chatted, dated, or politicked over 50 won coffee (paid with 14 hours of work).

“I couldn’t come here. It was too expensive,” remarks Shin Soon Ae, a sewing machinist at the time. In our 20s and 30s, we – a 3rd/2nd generation Korean-American, a 1.5 one, an adoptee, a 1.5 generation Russian-American, a Lebanese-Canadian, and a Canadian – are the youngest by decades. We planned to meet Shin Soon Ae to hear her story working at Pyounghwa Market and fighting in the Cheonggye Clothing Workers Union.

“There were three important periods in Korea’s modern history: Japanese colonization, the Korean War, and industrialization. My family suffered through each one. During Japanese colonization, the collaborators took my father’s land because of his involvement in the independence movement. He had to hide in the mountains where hunger would take a life-long toll on his stomach. During the Korean War, one of my brothers was the sole survivor in a helicopter crash, but not without injury. The other one was injured when a bomb exploded near him. They were all debilitated by various ailments. So, to supplement our income, I went to work. The only place that would hire a kid was Pyounghwa Market. I was thirteen.”

During the 1960s and 70s, Pyounghwa Market was the center of textile production in Korea. Merchants from all over the country would arrive to purchase clothes for retail or wholesale. There was unceasing demand, so factory owners would squeeze as many sewing machines and workers in their factories as possible. Female workers, as young as thirteen would work 14-15 hours a day with poor ventilation and few breaks.

After several attempts to improve working conditions, on November 13, 1970, during a protest rally, Jeon Tae Il, a twenty two year old cutter doused himself with gasoline and burned himself. As flames engulfed his body, he held a copy of the Labor Standard Laws and yelled, “We are not machines! Obey the Labor Standard Laws!” As he lay dying in the hospital, he pleaded that his death not be in vain. He was the worker movement’s first martyr and its spark. Two weeks later, his mother Lee So Seon and the Samdong Friendship Association organized the creation of the Cheonggye Union on the rooftop of Pyounghwa Market.

“I had already been at Pyounghwa Market 9 years when I joined the Choeonggye Union in 1974. Workers didn’t know what it was. They just knew that if you weren’t getting paid, you could go to the rooftop and get paid. As for me, I never graduated elementary school. I couldn’t afford it. So, when they were offering free middle school education, I decided to go. In the process, I was re-born a dignified and proud worker. People treated me differently at the union. At the factory, I was just “helper # 7”; at the union, people called me Miss Shin Soon Ae. At the factory, my eyes were constantly fixed on the machine needle to avoid getting punctured. I couldn’t look around me. Even when others suffered, my eyes remained fixed on the needle. But, when I came to class, people would treat me with dignity. I would look around and see friends. When I helped, people thanked me. I saw how things could be, and I learned that we were being exploited.”

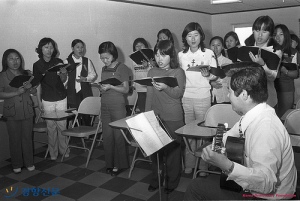

The Cheonggye Union represented workers in Pyounghwa Market. Its goal was the enforcement of the National Labor Standard. It organized and politicized workers through their Work Classroom which provided various after-work programs such as middle and high school level education, skills training, and cultural programs. This was a space of exchange where organizers (sometimes college students and faith based organizations) could raise workers’ consciousness around worker’s rights and demands while raising their own awareness around worker conditions and struggles.

“Before, the finish time wasn’t set. 12 a.m. was the start of the military curfew, so we would leave so as to get home before then. Some of us would leave at 11:00, others, at 10:30. It all depended on how long it took to get home, but if you worked until 10 p.m., you wouldn’t be able to attend the Work Classroom. This was because the classes were at 8:30 to 9:20 and 9:20 to 10:30. So, the union waged a struggle demanding that workers be let out by 8 p.m.. Our occupation started with 180 people, but as curfew approached, people left one by one. Despite the gun toting police, the threats of arrest, and red-baiting, 30 of us remained. The next day at 3 p.m., the factory owners accepted our demands. We were so exhilarated! We stood our ground and accomplished victory not just for ourselves, but for everyone.”

The Work Classroom’s activities educating workers and fighting for their rights made it a constant target of government attack. Only active worker struggles kept it open. In 1977, when the government attempted to close the Work Classroom, the workers waged a struggle against the police. As a result the solidarity between intellectuals and workers strengthened, and Bishop Ham Seok Heon, Ji Hak Soon, and 20 leaders would announce the establishment of the Pyounghwa Market Human Rights Association and the preparation for the Korean Charter for Human Rights.In 1981, the Cheonggye Union was disbanded by the government, but the workers fought to restore it.

“I felt the greatest hopelessness when the government forced the closure of our union in 1981. I became a fugitive for 2 years. Even afterwards, I was constantly under investigation and surveillance. People like Kim Dae Jung [who would become the first opposition leader elected president] were under surveillance, but people knew their suffering. I was just a simple worker, so no one knew about my persecution. The government offered me a job as an anti-North Korean propagandist. Even though I couldn’t get a job anywhere else, I refused. Then, they started sending me bags of rice. You got to know this was when it was hard. I still threw it out.”

In 1998, after continuing struggle, the union was re-established as the Seoul Regional Textile Manufacturing Union.

One of us teaching in a conservative region of Busan asks, “Some in Korea view the sacrifices during Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship as a necessary evil for Korea’s industrialization. What’s your response?”

“I ask you, ‘Who was sacrificed?’ If you owned a factory, you got rich. What about those that sacrificed? Where is their compensation? If sacrifice was necessary, alright. But, what about compensating and acknowledging our sacrifices now? Those that went to fight in the Vietnam War got something, they got acknowledged. But, we never got acknowledged. We never got compensated. The owners of the Pyounghwa Market and Park Chung Hee benefitted. Even if a little percentage of Korea’s GDP went to compensate those that had sacrificed, it would mean something. Some of my friends are ashamed of their past in Pyounghwa Market. They have hid their pasts from their families.”

As we finish our drinks and conversation at Myongbo Café, we start our tour of the Peace Market. We go to the 2nd floor of the Peace Market. While the original structures remain, the partitions that divided factories now divide retail stalls. We walk down the long narrow aisle between them. Shin Soon Ae points at a small attic above one of the sales stalls. “That’s where the sewing machinists would work. No matter how short you were, you couldn’t stand upright because the ceiling was so low. The cutters worked below.”

Pyounghwa Market runs the length of a long city block. It is partitioned into three areas with bathrooms in between. After we walk the whole length of the section and get to the bathrooms, Shin Soon Ae turns around to tell us, “These were the bathrooms for our whole section. All of us in our section had to use these bathrooms. So you can imagine when we needed to go to the bathroom we had to wait 20 to 30 minutes. We would go to the bathroom during lunch and then we’d only have 15 minutes to finish our food. That was one of the hardest things.”

As we exit Pyounghwa Market and cross toward Jeon Tae Il’s bridge, she motions across the main entrance towards the second floor. “Kookmin Bank was there. That’s where Jeon Tae Il doused himself with gasoline.” On the street below lies an inscription: “Here is the place where Chun Tae-Il shouted while his body burst into flames, ‘We are not machines. Abide by the Labor Laws!’ November 13, 1970.”

As we exit Pyounghwa Market and cross toward Jeon Tae Il’s bridge, she motions across the main entrance towards the second floor. “Kookmin Bank was there. That’s where Jeon Tae Il doused himself with gasoline.” On the street below lies an inscription: “Here is the place where Chun Tae-Il shouted while his body burst into flames, ‘We are not machines. Abide by the Labor Laws!’ November 13, 1970.”

We cross to the Jeon Tae Il bridge. She points at the brass inscriptions on the ground. “Mine is somewhere over there. We helped pay for this bridge with workers’ donations. Each brick cost 100,000 won.” As we stand in front of the statue of Jeon Tae Il, I ask, “What was Jeon Tae Il’s impact in your life?”

We cross to the Jeon Tae Il bridge. She points at the brass inscriptions on the ground. “Mine is somewhere over there. We helped pay for this bridge with workers’ donations. Each brick cost 100,000 won.” As we stand in front of the statue of Jeon Tae Il, I ask, “What was Jeon Tae Il’s impact in your life?”

“Whenever I was beaten up, or when I was suffering, I would think of him. ‘I am not dead like Jeon Tae Il.’ It put things into perspective, and it placed in us a sense of responsibility and guilt. After all, he had died for us.”

We finish our evening over grilled fish at “Restaurant of the Masses.” (Dongdaemun Market is known for its grilled fish.)

We finish our evening over grilled fish at “Restaurant of the Masses.” (Dongdaemun Market is known for its grilled fish.)

As she concludes our evening, I catch a glint in her eye, “Back when I was a textile worker here, I always wanted to eat at these grilled fish places, but I couldn’t afford it. Later, when I could afford it, I didn’t have the opportunity. Thanks to you, I get to eat grilled fish here for the first time and share my story.”

Lee Cheong Gak: “The Shit Water Baptism”

“I am the third daughter. My name means “bachelor.” It was so that I’d be the third and last daughter, and the next one would be a son. My father just drank at home, so my mother and sister worked, but even then we couldn’t manage three meals a day. When I was 18, I went to work for the first time. I worked in factories for 12 years until I was fired. “

“My sister went to work for Dongil first, then I went there. Dongil was bigger and better than other factories at that time. You could work in textile or lighter factories. Dongil was better than the lighter factory. It was really competitive getting a job there, so when I got hired, I was happy and proud. I could make money now and live like a human being, so I worked very hard. I was eighteen at the time. Dongil was a large factory so they had to obey the law. Still, people lied about their age using their sisters’ IDs, and the company just turned a blind eye.”

“We got paid by the piece, so we would try to work as much as possible. We would start at 8 a.m., eat lunch for 15 minutes, and then dinner at 10 p.m. Sometimes, when we had to meet a deadline, we would work 24 hours straight. The company ran three shifts: 5 a.m. to 2 p.m.; 2 p.m. to 10 p.m.; 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. You couldn’t eat when you worked, so you ate before and after. So people’s stomach would be ruined and because of the heat; we would develop athlete’s foot. To stay up, people would take stimulants.”

“There’s a song by Kim Min Ki about how when the boss’ dog gets sick, an ambulance takes it to the hospital while in the factories the workers toil away. Kim Min Ki went to work in the factories for a year to write that song. He wrote a song about a worker with six fingers. He received 50,000 won (about $50) for each of the four cut fingers, but because he was saddened, he drank it all away. At the end, not even the money was left.” Lee Cheong Gak starts to sing. There is no timidity in her voice, just emotion at singing the fighting songs of her youth. Cho Soon Young joins her. After the song ends, both laugh.

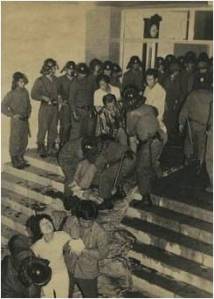

While 90% of its workforce was women, the leadership at the Dongil Union was dominated by pro-company men with little interest in the working conditions and wages of female workers. In 1972, women who had been involved in small group activities organized by the Urban Industrial Mission successfully organized to elect the first female president. Soon after, the company had male workers and the police to harass the women’s organizing efforts. In 1976, after male workers locked in the female delegates in their dormitories and elected a new male union president, the women staged a sit-in strike. On the third day, after the women resisted management’s efforts to draw them out by cutting the electricity and water, police were brought in to drag the women out. As they saw the police approaching, the women undressed thinking that “men cannot touch undressed women.” 500-800 naked women held each other tightly and sang union songs. In 1978, when an election was held for the union’s executive committee, pro-company male (and two female) workers splashed human excrement upon the women coming to vote. Its leaders, including Lee Cheong Gak, rushed with their stained clothes to a neighborhood studio to document the indignities they had suffered. It became the infamous “shit water baptism.” They would lose their struggle as the National Textile Union collaborated with the company to neutralize the women led union. Although 124 of its leaders were fired and blacklisted from taking jobs in other factories, their fierce fight inspired and fueled struggles such as the one at YH Trading Company.

We ask her what she thinks about the worker movement today.

“There is division among workers today – a division between regular and irregular workers. The workers of large corporations care only about their own wages. They need to support and struggle alongside the irregular workers also. Maybe the US and Northern Europe are different where there is not such a large gap between regular and irregular workers. But in Korea there is a big difference. Sometimes the regular workers negotiate contracts so that they can pass their regular worker job to their children. But the regular workers should be helping the irregular ones financially in their struggles. For example, in Incheon, there are two GM Daewoo factories a small and medium one. The KCTU has members in both the big corporations and the small and medium companies. However, when the workers in the small and medium enterprises wage a struggle, the ones in the big corporations don’t come out to support.”

Choi Soon Young: “Women Workers Brought Down Yushin”

“To understand Korean society you need to understand the Korean War and the industrialization that began at the end of 1960s. At that time we were a very different and poor country from the one we are now. Because our country was so poor, we sent people to Germany as workers and babies overseas for adoption. People had to come from the rural areas to the factories in order to make money. In Korean culture, they would send the son to school and the girls to the factories to help financially by working.”

“During that time Park Chung Hee made the lives of farmers very difficult. This was to create more workers and lower wages. During that time Korean workers, in particular women, were unskilled, so their advantage was their cheap labor. So, we see that during the 60s and 70s women were the majority of the workers in the large corporations. Back then Samsung and LG were clothing producers. During Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship Labor Standard Laws existed, but were not enforced. The worker’s union movement during the 70s was hard. The Christian groups, such as Christian Academy, did a lot. They worked to raise consciousness around religious reform, farmers, workers, and students. The idea was to train the leadership, and then when the leadership went back, they would educate others. At that time, the education that they received was considered radical and even shocking. Under Chun Doo Hwan we got red-baited. We would meet in small groups based on sectors, and learn theory through plays that we were one.”

YH Trading Company was a major exporter of wigs to the United States. It had been established with government financial support, yet, its managers were investing their profits in other companies. The major struggle against the YH Trading Company took place in 1979 when management announced that they would shut down the wig making plant, even after they had laid off half the workforce.

“During the end of the 1970s the repression against workers and farmers intensified, so the workers and farmers also started to intensify their protests. After we saw how they had broken Dongil Union, we decided that we would hold a last struggle regardless of whether we could win or not. We went to the New People’s Party building so that we could carry out a long term occupation struggle.”

On the third day of their occupation, a thousand police entered the building to remove the hundred or so workers. In the ensuing struggle, one of the union delegates, Kim Kyung Sook, was killed after falling from the fourth floor. The leader of the New People’s Party who had permitted the occupation was arrested.

“Because of that struggle lots of other workers also gained strength and inspiration. There were many other solidarity protests. The struggle at the New People’s Party exposed the Park Chung Hee dictatorship to the rest of the world. After that struggle Kim Yong Sam was incarcerated. This was a big deal because he was the leader of the opposition party. For someone of that stature to be incarcerated was a big deal. When Kim Yong Sam went on hunger strike, this got even bigger. The people in Busan and Masan protested because their representative had been locked away. Ultimately, it was an argument about how to deal with the Busan-Masan uprising within Park Chung Hee’s cabinet that led to Park Chung Hee’s assassination and the end of the Yushin Regime. So, the YH struggle sparked the series of events and protests that led to the fall of the Yushin Regime. Women workers brought down Yushin.”

Ripple Effect

This visit was part of the International Strategy Center’s Korean History, Economy, and Politics program. While the program centers on Korea’s social movement struggles and its protagonists, its purpose is to deepen participants’ understanding of Korean society and have them re-examine their relationship to it. As such, the participants are the other half of the program. Below are their thoughts:

“A month after watching the 70여공 play to commemorate March 8 Women’s Day, we met with the three former women garment factory workers whose stories were represented and retold in the performance. Hearing of their family backgrounds, how they came to work in the factories and their courageous struggles for a strong union and workers’ solidarity made the so-called ‘miracle’ of Korean industrialization come alive. I was inspired by the strong sense of unity, sisterhood and pride in their work that these women maintained, despite experiencing deep injustice from their workplace and their government. The personal oral histories have given me a much deeper understanding of who made the real sacrifice to make Korea what it is today, and why it is so important for women and workers to continue the struggle for representation in society.” – Ana Traynin

“Stepping back in time into a café with walls that have so much history was a unique experience. It was effective in connecting me to a past that I was not a part of. Touring the structure that once held the garment factories made the stories and history more tangible. It helped put the past into perspective. Listening to the three women talk about their lives and the struggles of the union was inspiring. Having the opportunity to ask questions in a more intimate setting gave us the chance to reflect on and clarify all the things we have learned so far. The dialogue the ISC is building between foreigners and Koreans is so important. It allows the stories and struggles of Koreans to reach and impact more people. The first step towards action is always education and dialogue.”– Erica Sweett

“This month’s meeting felt like a natural continuation of last month’s, when we watched the performance of ’70여공. At that time, I felt incredibly moved by the stories that each woman shared about her experience as a young factory worker and wanted to speak with them, but didn’t even know where to begin. This time, I knew far more about both the general history of Korea’s labor movement and each woman’s background, and was able not only to ask more meaningful questions but to better appreciate their answers. I had always thought of labor as being a male-oriented, male-dominated movement, but speaking with Shin Soon Ae, Lee Chung Gak, and Choi Soon Young opened my eyes to the central role women played in building Korea’s labor movement. Furthermore, many of them were in their early-mid twenties when they first joined the movement which, as a twenty-two-year old myself, I found incredible. I left at the end of the weekend feeling not only inspired by what they had shared, but with a sense of duty towards carrying on the spirit of their work in some way through my own.” – Stephanie Park

“Having the opportunity to meet and speak with these ladies was an incredibly humbling experience. The sacrifices they made and the passion they offered to their cause was -and continues to be- an inspiration to those who aspire to change their circumstances. I’ll never forget their stories, and I’ll carry their dedication with me into my future social justice work.” – Taryn Assaf

The World When Women Led Labor Unions in South Korea

A Reflection on Community Education

by Erica Sweett

Coming to Korea 1.5 years ago, I could never have imagined how much this country and its people could teach me. For me, education is about discovery. It is a shared knowledge that opens your mind to worlds beyond your own. Instead of passively learning about the culture and history of where we are living, we become active members of retelling and reshaping the future.

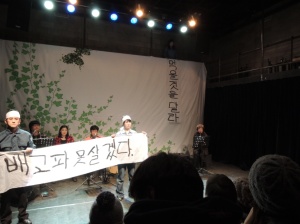

In March I was invited to see a play about three women who worked in the Korean garment factories during the 1970s. The women read their stories alongside actors who reenacted the scenes. Choking back tears, they spoke of the inhumane treatment, humiliation and violence they endured in the factories.

The Korea these women spoke of was not only of a different time, but of a completely different world. Their stories allowed me to see, from a personal perspective, the struggles many Koreans face.

The three women are political activists and organizers. Some are also mothers and grandmothers. They have taken on many roles during their lifetime have persevered and continue to fight for justice. I left the theatre inspired. These women could have easily buried their painful pasts; instead they had the strength to share their stories.

A couple of weeks later we met Shin Soon-Ae, one of the women from the play, in a Seoul cafe in Dongdaemun, located in the building that formerly housed the Cheonggye garment factories. After ordering some drinks, Shin told us more about the café’s past and that it hadn’t changed from the 1970’s. She took us on a small tour of the building and with her guidance, we were able to imagine a worker’s life here.

We also met with Lee Chung Gak and Choi Son Young, the other two women from the play. The three women told us about small church-based education programs and unions that led to their politicization. The programs allowed workers to become a part of a community where they were able to interact in small groups with their peers. These smaller interactions gave them a shared sense of pride and empowerment that inspired them to organize and take action.

This type of schooling was seen as a threat to the government and factory owners and was quickly shut down. A capitalist driven society does not value community education, but rather education that is driven by competition and individual needs. Small grassroots education programs posed a big threat to the oppressive leaders of the time. The action inspired by the educational programs proves that – while capitalism and dictator governments are powerful – so too are organized communities.

The ISC has given me the opportunities to engage in a way that wouldn’t have been possible on my own. They have introduced me to people and places that have challenged and broadened my understanding of the world. Through them I have started to connect more with Korea. I have become a part of a diverse community that is allowing me to reflect on my place, not only in Korea’s struggles, but the struggles of the global community.

These women have motivated me to infuse my life with more passion and to continuously question the knowledge I am acquiring. They identify as workers and have dedicated their lives to telling their stories. Learning in this way from our community is the first step towards becoming actively involved in a fight for change.

Reigniting the Spark

by A.T.

These days, most high-school-age Korean girls put on school uniforms and double over studying from morning to night, at the same rate as their male peers. As a visiting native English teacher in Korean high school, I’ve heard the word “hell” used more than once to describe these three years. However much they may hate it, for young people this remains the path to a kind of status denied to thousands of poor, rural girls growing up under Park Chung-hee’s military dicatorship of the 1960s and 1970s. Much of Korea’s economic progress, or the so-called “Miracle of the Han River” was carried out on the backs of workers like Shin Soon Ae of Cheongyye Union, Lee Cheong Gak at Dongil Textiles and Choi Soon Young at YH Trading Company.

As young women in the 1970s, Shin, Lee, Choi and their peers made up over 80% of the textile labor force. They sacrificed their youth, pouring into Seoul and Incheon to labor in factories and support their families. Instead of bending over textbooks, they spent their teens and early twenties bent over sewing machines in four-foot dusty attics. Sitting with these women in the quiet setting of Seoul cafes and hearing their stories from a distance of decades put a human face on cheap clothes and economic growth. It also revealed the deep-rooted context for the current labor repression under Park Geun Hye – the former Park’s first child and a woman roughly the same age as these three workers. The women’s personal histories make it clear who really made the sacrifice responsible for building Korea into a wealthy nation.

I’ve walked through Seoul’s huge Dongdaemun shopping district several times. I’ve bought clothes from one of the hundreds of small vendors. One warm summer night, as I walked outside after midnight, crowds and “Gangnam Style” were still jamming the streets. Dongdaemun’s late night shopping experience is one of Seoul’s prime tourist and fashion attractions but do any guides bother telling the history behind this after-hours cheap shopping party? Under the military curfew of Park Chung-hee’s industrialization regime, people were forbidden to be out in the street in the middle of the night. Instead, they stayed in the former bus terminal nearby and swarmed out at the break of dawn. Wholesale buyers and retailers from all over Korea would take the bus at 11 pm and arrive at Dongdaemun by 4 am just to get around the curfew. From this early bustling atmosphere, the late-night shopping mecca was born.

Just down the road from Dongdaemun’s shiny modern shopping malls, entering Pyeonghwa Market’s Myeongbo Dabang coffeeshop feels like stepping into another era. Usually, when I see the discreet “Dabang” signs, I assume these are just places for old men to hang out. I learned that back in the 1970s and 1980s, before the Starbucks, Caffe Benes, Tom n Toms and other chain coffee shops popped up all over Korea, places like Myeongbo served as prime meeting spots. Yet, as former Cheongyye Union worker Shin Soon Ae recalled with us over coffee, these same drinks were nearly off-limits for her and nearby workers, as they cost a full day’s labor. Myeongbo Dabang is where Jeon Tae-il held worker activist meetings before infamously setting himself on fire at the Pyeonghwa Market entrance on November 13, 1970. Knowing the prohibitive cost for workers, he bought drinks for everyone and made sure they could attend the meetings. Who knew that expensive coffee planted the seeds for Korea’s labor movement?

Shin, Lee, Choi and their sisters in the factories may have given up their formal education, but Jeon Tae-il’s sacrifice led to more than just the founding of the first workers’ union, the Cheonggye Union. It also led to the creation of a different kind of learning center – evening worker’s classes. Although, from day one, the unions had to fight merely to exist, through these classes they taught the female workers – who in the beginning didn’t know the meaning of a union – to organize and instilled in them a new sense of pride that couldn’t easily be taken away. Here, exhausted no-name laborers transformed into valued human beings who would eventually use their capacity to analyze and critique their situation to rise up against inhumane workplace conditions. While their peers in high schools and universities were busy learning facts, figures and national propaganda, these young women received education that made history, one that sowed the seeds of revolution that would lead to the end of Park Chung-hee’s rule.

Women struggling side-by-side also contributed to the ushering in of a concept that, according to Shin, the 1970s workers didn’t yet grasp – feminism. While burning in the streets of Seoul, Jeon Tae-il screamed “stop exploiting women!” Yet it was the women themselves who would fight this exploitation. Although they may not have viewed it this way, by organizing together with such strength and dignity, these women laid a strong foundation for the future of the Korean women’s rights movement. Lee Cheong Gak from Dongil Textiles recounted for us the shocking and unforgettable incident of being covered in human feces by male company thugs, simply for wanting to vote for a woman to lead their union. The response by Dongil’s female workers was equally unforgettable. By stripping half-naked, holding hands and forming a human wall against the riot police, they did something their male counterparts wouldn’t have the power to do. A single act set an irreversible precedent.

After Park Chung-hee’s assassination, Choi and Lee remember feeling a sense of elation. It didn’t last long, as the Chun Doo-hwan took power, companies busted worker-led unions, and members like Shin became jobless fugitives. Yet the 1980s saw the labor movement become infused with thousands of students, inspired by the previous decades’ struggles. Together, these powerful forces led the democratization movement that would transform Korean society.

With the current tragic events regarding the sinking of the Sewol ferry leaving Korea awash in a wave of mourning, many questions arise. They are not new questions, but they now seem especially pertinent. Under a capitalist system, what is the worth of one human being? Workers, as well as dead bodies, are assigned numbers. With so much technological progress, where are we really going? Towards societies that overcome the unequal structures of the past – or ones that value speed and the bottom line over peoples’ safety and well-being? Since the 1980s, when Korean students joined the labor movement to organize for democratization, it seems that the country’s compass has swung in the other direction – towards complacency and a fight for status and success instead of freedom. Perhaps now that corruption and carelessness have been revealed in such an ugly way, these questions will again begin to spur collective action that inspires international movements, as Korean workers and activists have done in the past. Perhaps it’s time to reignite the spark.

“Enforce the labor code! We are not machines!”

by Stephanie Park

Anyone with a passing knowledge of Korea’s labor movement knows the name of Jeon Tae Il, the iconic young male worker who self-immolated in protest of working conditions in Korean factories during the 1970s, as well as the words he shouted that fateful day in Seoul’s Pyeonghwa Market. I first learned about Jeon Tae Il through a college class on Korean cinematography, where we watched A Single Spark, a film that dramatizes his life and the events that led him to such drastic action.

The film and its protagonist made a huge impact on me; not only was it my first introduction to Korea’s labor movement, but it proved to be a key part of my burgeoning political consciousness and interest in Korea. However, a crucial fact that I remained ignorant of until just a few weeks ago is that, although Jeon Tae Il may have provided the ‘single spark’ that set the labor movement of the 1970s in motion, the movement was by and large comprised mainly of female laborers.

As a graduate of a women’s college, I was both shocked and awed by the revelation. Throughout the weekend, we met and spoke with three former women laborers who spent the 1970s entrenched in the movement: Shin Soon Ae of the Cheonggye Clothing Workers Union, Lee Chung Gak of Dongil Textile Union, and Choi Soon Young of the YH Trading Corporation Union. Their stories impressed upon me the need to reclaim and assert our humanity in the face of systematic dehumanization of the industrialized world. What makes a worker decide to unionize, especially given the formidable threat of retribution promised by one’s factory and government? How does a labor force of women resist? And how can this history help me to understand the forces that shaped my own family’s history?

When Jeon Tae Il voiced his now-famous sentiment “We are not machines!” he challenged laborers not only to remember what they were not, but also what they were. In the case of female laborers, this meant recalling and reclaiming their humanity in the face of systematic dehumanization day in and day out at the factory.

Considering the way factory life was structured in order to mimic machinery as closely as possible – leave for work at 6:30am, scarf down lunch in the 10-15 minutes that remained of one’s lunch break after waiting to use the bathroom, and back to work from 1-11:20pm, with no water or bathroom breaks allowed – this was a feat in and of itself.

A well-known joke, based on a pop song by Kim Min-Ki, was that the boss’ dog had a better chance of being hospitalized than any female laborer. However, most dehumanizing was the fact that the women were not referred to by name, merely a combination of job designation and number such as “helper #5” or “machinist #3.” In this way, their individual identities were erased and they came to be defined solely by their utility in service to the factory. Maybe this is why Shin Soon Ae’s recollection of how she joined the labor movement is so unforgettable: “When I went to Work Classroom I became ‘Ms.’ Shin Soon Ae. I was so moved to be treated like a human being.” In contrast to the ruthless impersonality of factory life, how monumental it must have felt to have been recognized and valued as an actual human being!

The profundity of taking ownership of one’s humanity becomes so only after one’s eyes become opened to the naturalization of exploitative and dehumanizing labor relations, particularly in the face of organized resistance like that of Korea’s female workers, or ‘70여공. I had assumed that, like Jeon Tae Il, most male laborers were sympathetic to the plight of the female workers. After all, many women turned to factory work to provide for their families, brothers, husbands, and fathers included. Yet at Dongil Textile, it was most often male workers responsible for the most horrifying acts of intimidation and violence against female workers and their attempts to unionize. From locking their female coworkers in a dormitory without water or food, to smearing them with human excrement, to even physically injuring them, what was it that made these men see these women as subhuman, and not the sisters, wives, and mothers they were? If, as factory conditions and pressures of industrialization took great pains to teach, ‘70여공 were only as good as their cheap and unquestioning labor, perhaps it’s not that outrageous after all. After all, if people today can say and believe (as they do) that the sacrifice of a few was necessary for the good of all in creating Korea as a modern nation today, is that not violent and dehumanizing in its own way?

Most shocking of all, however, is that, in the face of this overwhelming violence and repression, the workers’ response was to make themselves even more vulnerable; in doing so, they brought conviction in their own right to humanity to the forefront and challenged the rote process of dehumanization that had become a given. An iconic example of this occurred at Dongil Textile when, in response to the arrival of riot police to break up a three-day strike, women workers stripped naked to the waist and confronted the police face-to-face. As worker Suk Jung-nam recalled,

“In the face of such an enormous threat of violence, it was our ultimate resistance, an action spontaneously taken, with no shame or fear. Under siege by the armed police and male workers, we hung tightly together in our nakedness. Can steel be stronger and harder than this? Who dares to touch these people?”

When faced with certain violence, my last instinct is to make myself even more vulnerable. Yet it is for this very reason that I find the response so revolutionary, as a powerful reminder of the humanity we are conditioned to forget.

One consequence of such conditioning can be the erasure of our own histories. Throughout the weekend, I found myself drawing comparisons between the women workers and my own maternal grandmother; as she is of comparable age to the women we met and possesses her own complicated relationship with labor, I couldn’t help but think of her. In particular, I found myself drawing parallels between her life and that of Shin Soon Ae.

Both grew up fairly prosperous in the Jeollabukdo region near Jeonju; both grew up in relative prosperity before seeing their family’s fortunes disintegrate with the arrival of Japanese imperialism; and both entered the labor force for the sake of their families (Shin Soon Ae to support her family after the war, and my grandmother to support her husband and sons after immigrating to America). Her words helped me understand a little better what it must have been like for my grandmother, and contextualized the health problems she suffers from today.

Unlike Shin Soon Ae, however, my grandmother never joined a union, instead working tirelessly and silently at odd jobs that didn’t require much English until she had enough money saved to start a modest sandwich business. Furthermore, while Shin Soon Ae, Lee Chung Gak, and Choi Soon Young have made it their mission to share their stories publicly, my grandmother’s story has gone largely untold. I have only begun to learn about my grandmother’s past and the hardships she faced in the past two years – and the process of retelling and thus reliving such times have been exhausting for her. Similar to some of Shin Soon Ae’s friends, whom she says still feel shame at being or having been a laborer, I sometimes sense a similar shadow of silence obscuring my family’s history.

As a child, I crept around subjects such as this, which I knew better than to ask about. But after spending time with Ms. Shin, Lee, and Choi, and seeing what can come of taking ownership of one’s story, I wonder what good such silence has done for my family. In any case, I can’t change the past, but I can impact the future. As Shin Soon Ae reflected on her legacy, one of the things that seemed to matter most was that her granddaughter be educated about the history of the labor movement. My grandmother lived a country away, was not part of a union, and perhaps wouldn’t have been even had she worked at Pyeonghwa Market, Dongil, or YH. But there’s value in both narratives, and in learning them, I feel compelled to carry them forward and keep the spark alive.

ISC Research Paper: Global Movement for Higher Minimum Wage and the Real Situation of Korean Companies Operating Abroad

Recently, demonstrations have been breaking out around the world demanding an increase in the minimum wage. This is the result of wages that have remained too low since the financial crisis exacerbated by the continuous inflation along with exchange rate increases which have made it impossible to guarantee a minimum standard of living. According to the “Global Wage Report 2012-13” by the International Labor Organization (ILO), the global average real wage (excluding China) has not increased since the 2008 financial crisis. Minimum wage became a big issue not only in Asia, known as the world’s factory due to its cheap labor but also in the US and the UK. In the US, the movement is spreading propelled by fast food workers. In the UK, the average real wage dropped 13.8% after the 2008 financial crisis prompting the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), one of the UK’s leading independent employers’ organization, to demand a pay raise.

Download the full report here

Everyone Has the Right: An Interview with Nazmul Hossain from the Migrants Trade Union

Written by Kellyn Gross

Interview by ISC Media Team

“Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” -Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 14(1)

On December 15, the ISC media team attended the 2013 Migrant Workers Assembly at Seoul City Hall’s Annex Building. The conference was in commemoration of International Migrants Day, and migrants were in attendance from such countries as the Philippines, Mongolia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Participating organizations included the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), the Alliance for Migrants Equality & Human Rights, the Joint Committe with Migrants in Korea (JCMK), the Gyeonggi Alliance for Migrants’ Rights, and the Incheon Alliance for Migrants’ Rights.

Before the assembly, we sat down with Nazmul Hossain, the Incheon branch secretary of the Migrants Trade Union (MTU). The Migrants Trade Union started in 2005 and is included the KCTU.

Hossain is a refugee in Korea from Bangladesh, where he feared for his life from police reprisal due to his student activitism. He holds a refugee passport issued from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Although Korea has been a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees since 1992, it has failed to abide by the convention’s protocols. Particularly, Korea hasn’t given “sympathetic consideration to assimilating the rights of all refugees with regard to wage-earning employment to those of nationals, and in particular of those refugees who have entered their territory pursuant to programmes of labour recruitment or under immigration schemes”[1].

Hossain initially came to Korea eight years ago on an international trainee visa. He then applied for and was granted refugee status by the UNHCR. Yet the Korean government has denied him basic protection as an asylum seeker, and his trainee visa has since lapsed. He has chosen to remain in Korea as an undocumented worker rather than leave the country and risk deportation back to Bangladesh. He, like many others, are thus left in stateless limbo. Of the about 4,700 people who have applied for refugee status here since 1992, Korea has only approved about 300 applications. This six-percent figure is dismally low.

We discussed migrants’ fight for equal labor rights in Korea with Hossain, as well as MTU’s call for an end to the government crackdown of undocumented migrant workers and their continued exploitation under the Employment Permit System (EPS).

ISC: Can you give us a brief background of yourself? When did you come to Korea, and how did you get involved with the migrant workers trade union?

Nazmul Hossain: I will talk about my past myself. In 2006, I came to Korea under an international trainee visa. But the Korean labor situation is very hard. Labor is low-standing, and there are many problems. The Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor gives no benefits to laborers outside of just work. That’s all. Work, sleep, some food, a workplace and nothing else.

In 2008, the Korean international trainee laws changed into the EPS. But the EPS is in the same category, with problems remaining because foreign laborers in Korea are given very hard work for no salary. The situation is impossible because migrant workers are given little money for a lot of work.

What is the international trainee visa like?

The international trainee visa promises foreign students work training if they come to Korea. But in the end, this is impossible. Instead it’s, “Come to Korea! But labor.” The Korean government says training isn’t a right. There is only the right to do labor.

So they aren’t actually offering any training? You just have to work?

Yes. International trainees can only be in Korea for one year. I first came to Korea for training in engineering things like this microphone, and mechanical training in general. I came to Korea for training, but I only labored. When you go to a Korean company, you only labor. No training is given. Just labor. The salary is the same, but the Korean government issues no training certificate. And I’ve asked this since my arrival, why didn’t the Korean company give me my certificate? Why doesn’t the government give me my certificate.

What were you coming to be trained for?

In 2008, I came to Korea for the same reason that others do, to be trained in something and return to my country in order to open a factory or branch of the Korean company that I trained under. But when we come, we just do common labor.

What did you want to train in?

It wasn’t about any particular skill but the promise of learning a skill that I could take back to my country, and then from there build a factory or start something based on that skill. Yet no certificates are given, and trainee workers are just working.

What is the work?

CNC machining. We were using CNC machines to make machine parts like pistons and gear boxes.

(CNC stands for computer numerical control, essentially computer-controlled machines making parts for other machines.)

Also, EPS is the same thing as the international trainee visa without the promise of going back to your country and building a factory. And Korea’s labor promise to foreigners is now work for four years and ten months.

Why four years and ten months? Why not five years?

Because if you live in Korea for five years, you can legally apply for permanent residence.

So the visa is for four years and ten months, two months shy of five years.

Yes.

In Korea, workers are not thought of as people, but are thought of as machines. Like robots. How can people work for 12, 13, 14 hours?

Migrant workers can be in Korea for up to four years and ten months. But it’s very difficult to come back to Korea after this time period.

Why do you think they make it difficult for you to come back?

It’s because if you are here for longer, you could have permanent residence. It’s just the legality of the system.

So, migrant workers’ activities are currently campaigning to be able to bring their families to Korea. And they believe that regardless of what your status is—whether you are undocumented or documented—you should be able to get legal residency after living here for ten years. That way, workers can live well in Korea.That’s the struggle people are waging.

The five-year rule doesn’t apply to me, even though I’ve been here eight years because of my undocumented status.

And my labor union, MTU, isn’t legally recognized yet, although our case is at the Supreme Court. If we’re legally recognized as a union, then we have legal recourse at the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

I hope you can understand me. Korea doesn’t have human rights. The Korean government tells all other countries that human rights are good here, but it’s impossible. There are no human rights for workers.

Not in reality, just talk.

Yes. Korea has 7,000 refugees, but only 270 people are legal. Almost seven thousand people are illegal! So, they can’t work. It’s a very hard life for refugees in Korea.

Do you want to live in Korea permanently? What are your future goals?

(Gesturing to his UNHRC passport) Actually, I want to leave. But this passport isn’t acceptable in Korea. I can’t get through airport immigration to go to another country. I can’t go outside Korea legally with this passport.

You haven’t left Korea?

No. I’m living in this country because Korea doesn’t have human rights.

What country would you like to go to?

Oh, the US, Canada, France, Spain because these countries’ human rights are very good. Many refugees are living in these countries, I know, but I like these countries. I like Korea, but Korean law is very hard. No human rights here, only talk.

I went to the Ministry of Justice office and told them I wanted to leave Korea, and they said I can’t with this passport. Then I said I wanted to legally live here, and I asked for a residency visa permit. But they wouldn’t give me one. So, how can I live? They just said to wait.

The problem is that because Korea doesn’t accept my asylum status, they would just return me back to Bangladesh. So, I can’t leave Korea, while at the same time, I can’t live here in Korea because of the human rights conditions and my illegal status.

I share this information, while countrywide newspapers say there is no problem. Korean law states that I have 100-percent rights. Yet currently, 7,000 refugees have very hard lives and are in hard situations right now. I hope US, Canada, France and Spain—all countries push Korea to protect human rights and accept refugees.

Can you tell us about the history of the MTU? And what do you do at the MTU?

I told you previously about how I came to Korea, and how the labor situation was hard. And I thought about why. Why did Korea not give international trainees rights? I went to the Ministry of Labor office and asked this question, why not give trainees rights? The office said that this is how it does things, and it can’t change it.

I joined MTU as a migrant worker in Incheon in 2008, and the MTU itself started in 2005. I came because there were a lot of problems with the labor law. I couldn’t change things working by myself, but I knew I could change things with others in an organization. MTU is the only migrant union in Korea.

Korea has a lot of factories, and it needs workers. Bangladesh has a lot of people, and not much work. So, this is why people come to Korea. The wages aren’t high in Korea, maybe a little over one million won per month. But as long as there isn’t work in other countries, people will keep coming to Korea. Because of that, the Korean government isn’t giving migrant workers benefits or honoring human rights.

So, they’re taking advantage of the fact that there are impoverished people looking for work.

Yes. In ten years, if the laws don’t change and if there aren’t labor rights in Korea, then workers will stop coming here. And if there is no one to work the machines, then Korea won’t do well.

Already, the MTU president has submitted different legal documents requesting changes in the law. We don’t know when changes will occur, but we’ll persist until the changes happen.

Do people in Bangladesh or other countries know about these conditions? Do governments still project the idea that it will be beneficial for them to learn things here?

There are no workers from India who come here. The reason why is because the Korean government doesn’t offer training certificates.

Does the Bangladesh government have an arrangment with the Korean government?

No. People don’t know that human rights are absent in Korea. It’s impossible, and I’m only one person. I hope that next time people like you can help spread the news.

Yes. And we had a question about how men and women migrant workers are affected differently?

Men and women work equally hard in Korean companies. People are too busy working to think about anything else.

When you have worked in factories, were you working with men and women?

Yes, all together. No problem.

Do women have more problems as migrant workers, or the same kinds of problems as men?

All migrant workers have one problem, which is a lack of labor rights.

What are some of the daily struggles that you see or experience on the job?

I don’t know when we’re going to stop the work that we do, whether it’s in 20 or 30 years. No one knows when we’re going to achieve our labor rights, even though things have gotten better since MTU started. There are still a lot of issues, like people not getting paid, or people not being taken to the hospital when they are sick. So, we’re going to keep struggling.

This piece is from the ISC media team’s conversation with Nazmul Hossain. His statements and ours have been edited not for obfuscation but for clarity due to a language barrier.

[1] Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Duipuri- A Short Story

by Kellyn Gross

“Geonbae!”

“Bottoms up.”

He raises his shot glass in the air, striking hers as she does the same. Soju spills, dripping onto a stained blue checkered tablecloth. A sudden laugh escapes her pursed lips. She downcasts her eyes and smooths her pants. Her pale make-up no longer conceals her flushed face.

“To us!” The young man brings the glass to his lips, and tilts his head back as he gulps the clear liquor. His plastic stool wobbles, and he clasps the round table to brace himself. Unsuccessful, he falls against the orange tent wall. A broad smile forms on his round face, and he gingerly places his glass down.

“To us.” A loose bun at the nape of her neck unfurls. She pats it with her left hand. The young woman sips down her drink and smirks.

It’s four o’clock in the morning and cold. Yellow traffic lights flash through the tent’s clear, plastic windows, and smells of frying oil, cigarettes and booze linger. The man sets two empty soju bottles upright and pushes them across the table to join another three. They clang and fall over again. The woman picks up each of the four charred skewer sticks and tosses them into the small garbage tin by their feet. They are the only diners in this street food stall.

“More side dishes and another soju. Oh, and four more fish cake skewers, please.” He waves at the old woman sitting behind steaming vats of broth and skewered meats. The squat proprietor slides her blanket off her lap, slowly stands up and limps past the counter to a fridge lined with bottles of soda, soju, rice wine and beer. He looks at her stooped frame and dashes to her with the empty dishes. Their eyes scarcely meet.

“Thank you.” The man bows earnestly as he takes the bottle from her.

“Yes.” She returns to her station to refill the dishes, occasionally stopping to listen to the radio drama droning on behind her.

“I’m glad you asked me to join you.” She sighs and hugs her coat lapels close to her chest as he sits back down. “You saved me from drinking alone.”

“I’m glad you said yes. So, do you think we have drank enough to forget our problems?” He twists the soju cap off with a quick motion and tips the bottle toward her. She holds her glass with two hands and accepts his pour.

“No, but maybe after this one.” They both laugh, and she pours a drink for him as well. She looks at his scuffed fingernails and the dirt smudges on his hands. “You said that your family is from Taegu, right?” Her hands are smooth and clean.

“Yes, Taegu. But I moved to Seoul about six years ago. My mom was working here first.”

“Tell me more about Peace Market. Do you like your job?” His wide-set eyes steady on her in silence before he looks down. He doesn’t wait for a toast and drinks the entire shot.

“No, I don’t.” The old woman returns, placing dishes of dried squid, chili pepper sauce, peanuts and a plate of four fish cake skewers on the table. He pours himself another shot and knocks it back.

“I usually have to work 14 hours a day, and I even work on Sundays. Work starts in a few hours, really. But we aren’t paid overtime. The seamstresses operate the sewing machines until late at night. They all have health problems. They’re only middle-school girls, working 15 hours a day.”

“Middle-school girls?”

“Yes. I don’t know how they can stand it. There is no ventilation, and the fumes are horrible. They can’t afford to eat more than a bowl of ramen a day. Hell, neither can I most days.” She wrings her hands, and her eyes search his face for answers to these troubling stories.

“You look cold. Here. Take my jacket.”

“No, I’m okay. I’m just shocked by this information.”

“Please. I insist.” He removes his brown jacket and drapes it over her shoulders.

“Thank you.”

“It’s my pleasure.”

“So, do you operate the sewing machines, too?”

“No, I’m a fabric cutter. I get extra money for the job, but it’s very little.” He stuffs a skewer in his mouth and rakes off the fish cake with his front teeth. “The shop I work in is no bigger than this pojangmacha.” He gestures toward the tent walls with the skewer, then sees she isn’t eating. “Please, help yourself.” She takes the skewer from his outstretched hands and spins it between her fingers before eating the fish cake.

“Thanks. Have you tried telling labor inspectors?”

“I’ve tried, but they just say they’ll inspect shops and never do. I say to them, we’re not machines! But they don’t listen. Why should they? Even our president ignores labor regulations. Which reminds me, I bought a copy of the Korean Labor Standards Act.”

“What’s that?” She takes another skewer and nibbles the sides of the fish cake.

“The act is supposed to protect workers and their rights. I’m teaching myself hanja to read the document, but it’s difficult and slow. I wish I had a university friend to help me. Do you know how to read hanja?” She is not only studying at Sogang University, but she studied hanja throughout primary and secondary school.

“N-no I don’t. I-I-I’m really sorry I can’t help you.” Her lips barely move, and she is almost inaudible.

“That’s okay. It’s all in the act, though. Workers are guaranteed proper wages and eight-hour workdays by law, as well as Sundays off and regular health exams. But I’m learning that the law is nothing but a piece of paper.”

“It’s not right.”

“No, no it’s not. And it keeps me up at night. What about you? You still haven’t said why you were drinking alone on a Saturday night.”

“Nevermind. It’s nothing, really.”

“No, I want to know. I’m listening.” He peers at her as she fiddles with her skewer.

“First, let’s toast.” She quickly chews the last bite of fish cake.

“Oh, of course. Cheers! To workers!” The fabric cutter pours himself another shot, and together with the university student, they raise their shot glasses in the air. Soju spills again onto the stained tablecloth before the glasses reach their mouths.

“So? What’s worrying you?” She hesitates to respond and then peeks at her silver wristwatch.

“You know, it’s almost 5am. I should go home. Can we talk about this another time?”

“Uhh. Of course. Do you live nearby? I can walk you home.”

“I’d rather walk alone if that’s okay. Not that I haven’t appreciated my time with you, but it’s more proper this way.”

“Okay, I understand. So, I guess this is good night? Or good morning?” He chuckles.

“Either way, I guess it is. First, I should give you some m—”

“No, I’ll pay.”

“But I drank and ate just as much as y—”

“No, I’m your older brother. I was born in 1948, remember?”

“I remember, I just thought—”

“Really, it’s okay.”

“Well, thank you so much for your kindness.”

“You’re welcome.” He pulls out a handful of coins from his front pocket and approaches the old woman at the counter. Their eyes still scarcely meet.

“Here you are. We ate well. Thank you.”

“Yes. Come again.” The young man and young woman exit through the front door and face each other on the sidewalk.

“Let’s meet again.” He shoves his hands in his pockets.

“Okay. When and where?”

“How about here next Saturday? But let’s meet in the afternoon instead.”

“Yes, good thinking.” She teeters back and forth on her heels to stay warm in the chilly November air.

“Well, nice to meet you, and I’ll see you in a week. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye.” She smiles and bows. He smiles in return and hurries down the sidewalk toward the orange glow of sunrise at the street’s horizon.

Good-bye. Wait.

“Hey! I don’t know your name! I still have your jacket!” She starts to run after him.

“Aaeesh! Yelling won’t help. He’s gone. Besides, you’ll see him again.” The old lady clucks her tongue, arms akimbo. She limps past the plastic doorway to sit once again behind vats of broth and fried food.

The young woman stops. She places her hand above her heart, tracing the edges of a name tag with her finger. She looks down and reads the white letters set against the black background.

“Jeon Tae Il.” Smoke from the tented restaurant wafts in the air. The old woman turns up the volume on her radio. The red sun rises over the cemetery, and the sweltering midday heat is my hardship. Now, I leave to the wilderness. Leaving all sorrow behind, now I go.

Park Geun Hye is startled awake. She’s in her arm chair on the second floor of the Blue House.

Am I smelling smoke? Her cellphone rests on a table next to her. She picks it up and speed dials her assistant.

“Tomorrow morning is a national labor rally in memory of Jeon Tae Il, no?

“Yes, Madam President, that’s correct. Unions will be mobilizing tomorrow at City Hall, although the exact date of his memorial is November 13th. Forgive me, but if you were considering trying to visit the Jeon foundation again, I think that given what happened last y–”

“No, I won’t be attempting to visit the foundation. But I did promise last year at his monument to make a country where laborers are happy.”

“I see, Madam President. I’m not sure w–”

“What time are protesters gathering tomorrow?”

“I believe at ten o’clock. Approximately 200 combat police and riot control personnel will be on stand by surrounding the US embassy per protocol. Would you like to speak with Mayor Park Won Soon and suggest a stronger police presence?”

“No, I most assuredly do not. But do arrange a car pick up for me at eight o’clock en route to City Hall.”

“But, Madam President, I don’t think that’s possible. Tomorrow is Sunday, and you have your weekly security meeting with advisor Chun Yung Woo.”

“Well, call him to reschedule for Monday. I also want to contact labor organizers tonight. Can you help me do that? Can you get KTCU members or Ssangyong Motors people on the phone?”

“I can try, but Madam P–”

“Good. I want to speak with any labor representative whom I can. And I need to address the protesters tomorrow.”

“B-b-but Madam President, this is highly unorthodox.”

“I know. But I made a promise to workers. An-an-and I just haven’t done that. It’s time I did.”

“Madam President, I’m sorry, but I don’t understand this. I mean, why?”

“Why? Because I want to be the friend to workers my father wasn’t before—that I wasn’t before. As you know, my memorial business has always been to my father.”

“Yes, Madam President, of c–”

“But my memorial business should include workers like Jeon Tae Il who have made great sacrifices.” She stared at her father’s solemn portrait on the far wall, then gazed out the window.

“It’s taken a single spark, and it can’t be put out.”

This fictional story was inspired by the workers’ rights activist Jeon Tae Il and by the Worker Day Gathering that the media team attended on November 9th. Jeon Tae Il committed suicide by self-immolated on November 13, 1970 to protest horrendous working conditions in garment factories under Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship. His struggle lives on in the labor movement’s fight against Park Geun Hye’s policies.