by Dae-Han Song

Among the key worker struggles during the Yushin Regime of Park Chung Hee were those waged by women at the Cheonggye, Dongil, and YH Unions. After watching the play 70 Women Workers by the Arts Collective for a New Era, we spent a weekend meeting up with its three protagonists. Our first day, we got a tour of Pyounghwa Market (the primary textile district in Korea) by one of its then-organizers Shin Soon Ae. Our second day, we sat down at a Gwanghwamun café to talk with Lee Cheong Gak and Choi Soon Young presidents of Dongil and YH Union during its most intense and fierceest struggles.

Shin Soon Ae: A Born Again Worker

Walking into Café Myongbo (Treasure) is like walking into the 70s. The walls and upholstery are stained with the past, and its

customers are now aged. Shin Soon Ae, a movement elder and once unionist at Pyounghwa (Peace) Market, suggested the café; Korean labor martyr Jeon Tae Il and his Samdong Friendship Association held their meetings here. It was a hip place where young people chatted, dated, or politicked over 50 won coffee (paid with 14 hours of work).

“I couldn’t come here. It was too expensive,” remarks Shin Soon Ae, a sewing machinist at the time. In our 20s and 30s, we – a 3rd/2nd generation Korean-American, a 1.5 one, an adoptee, a 1.5 generation Russian-American, a Lebanese-Canadian, and a Canadian – are the youngest by decades. We planned to meet Shin Soon Ae to hear her story working at Pyounghwa Market and fighting in the Cheonggye Clothing Workers Union.

“There were three important periods in Korea’s modern history: Japanese colonization, the Korean War, and industrialization. My family suffered through each one. During Japanese colonization, the collaborators took my father’s land because of his involvement in the independence movement. He had to hide in the mountains where hunger would take a life-long toll on his stomach. During the Korean War, one of my brothers was the sole survivor in a helicopter crash, but not without injury. The other one was injured when a bomb exploded near him. They were all debilitated by various ailments. So, to supplement our income, I went to work. The only place that would hire a kid was Pyounghwa Market. I was thirteen.”

During the 1960s and 70s, Pyounghwa Market was the center of textile production in Korea. Merchants from all over the country would arrive to purchase clothes for retail or wholesale. There was unceasing demand, so factory owners would squeeze as many sewing machines and workers in their factories as possible. Female workers, as young as thirteen would work 14-15 hours a day with poor ventilation and few breaks.

After several attempts to improve working conditions, on November 13, 1970, during a protest rally, Jeon Tae Il, a twenty two year old cutter doused himself with gasoline and burned himself. As flames engulfed his body, he held a copy of the Labor Standard Laws and yelled, “We are not machines! Obey the Labor Standard Laws!” As he lay dying in the hospital, he pleaded that his death not be in vain. He was the worker movement’s first martyr and its spark. Two weeks later, his mother Lee So Seon and the Samdong Friendship Association organized the creation of the Cheonggye Union on the rooftop of Pyounghwa Market.

“I had already been at Pyounghwa Market 9 years when I joined the Choeonggye Union in 1974. Workers didn’t know what it was. They just knew that if you weren’t getting paid, you could go to the rooftop and get paid. As for me, I never graduated elementary school. I couldn’t afford it. So, when they were offering free middle school education, I decided to go. In the process, I was re-born a dignified and proud worker. People treated me differently at the union. At the factory, I was just “helper # 7”; at the union, people called me Miss Shin Soon Ae. At the factory, my eyes were constantly fixed on the machine needle to avoid getting punctured. I couldn’t look around me. Even when others suffered, my eyes remained fixed on the needle. But, when I came to class, people would treat me with dignity. I would look around and see friends. When I helped, people thanked me. I saw how things could be, and I learned that we were being exploited.”

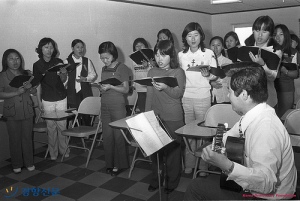

The Cheonggye Union represented workers in Pyounghwa Market. Its goal was the enforcement of the National Labor Standard. It organized and politicized workers through their Work Classroom which provided various after-work programs such as middle and high school level education, skills training, and cultural programs. This was a space of exchange where organizers (sometimes college students and faith based organizations) could raise workers’ consciousness around worker’s rights and demands while raising their own awareness around worker conditions and struggles.

“Before, the finish time wasn’t set. 12 a.m. was the start of the military curfew, so we would leave so as to get home before then. Some of us would leave at 11:00, others, at 10:30. It all depended on how long it took to get home, but if you worked until 10 p.m., you wouldn’t be able to attend the Work Classroom. This was because the classes were at 8:30 to 9:20 and 9:20 to 10:30. So, the union waged a struggle demanding that workers be let out by 8 p.m.. Our occupation started with 180 people, but as curfew approached, people left one by one. Despite the gun toting police, the threats of arrest, and red-baiting, 30 of us remained. The next day at 3 p.m., the factory owners accepted our demands. We were so exhilarated! We stood our ground and accomplished victory not just for ourselves, but for everyone.”

The Work Classroom’s activities educating workers and fighting for their rights made it a constant target of government attack. Only active worker struggles kept it open. In 1977, when the government attempted to close the Work Classroom, the workers waged a struggle against the police. As a result the solidarity between intellectuals and workers strengthened, and Bishop Ham Seok Heon, Ji Hak Soon, and 20 leaders would announce the establishment of the Pyounghwa Market Human Rights Association and the preparation for the Korean Charter for Human Rights.In 1981, the Cheonggye Union was disbanded by the government, but the workers fought to restore it.

“I felt the greatest hopelessness when the government forced the closure of our union in 1981. I became a fugitive for 2 years. Even afterwards, I was constantly under investigation and surveillance. People like Kim Dae Jung [who would become the first opposition leader elected president] were under surveillance, but people knew their suffering. I was just a simple worker, so no one knew about my persecution. The government offered me a job as an anti-North Korean propagandist. Even though I couldn’t get a job anywhere else, I refused. Then, they started sending me bags of rice. You got to know this was when it was hard. I still threw it out.”

In 1998, after continuing struggle, the union was re-established as the Seoul Regional Textile Manufacturing Union.

One of us teaching in a conservative region of Busan asks, “Some in Korea view the sacrifices during Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship as a necessary evil for Korea’s industrialization. What’s your response?”

“I ask you, ‘Who was sacrificed?’ If you owned a factory, you got rich. What about those that sacrificed? Where is their compensation? If sacrifice was necessary, alright. But, what about compensating and acknowledging our sacrifices now? Those that went to fight in the Vietnam War got something, they got acknowledged. But, we never got acknowledged. We never got compensated. The owners of the Pyounghwa Market and Park Chung Hee benefitted. Even if a little percentage of Korea’s GDP went to compensate those that had sacrificed, it would mean something. Some of my friends are ashamed of their past in Pyounghwa Market. They have hid their pasts from their families.”

As we finish our drinks and conversation at Myongbo Café, we start our tour of the Peace Market. We go to the 2nd floor of the Peace Market. While the original structures remain, the partitions that divided factories now divide retail stalls. We walk down the long narrow aisle between them. Shin Soon Ae points at a small attic above one of the sales stalls. “That’s where the sewing machinists would work. No matter how short you were, you couldn’t stand upright because the ceiling was so low. The cutters worked below.”

Pyounghwa Market runs the length of a long city block. It is partitioned into three areas with bathrooms in between. After we walk the whole length of the section and get to the bathrooms, Shin Soon Ae turns around to tell us, “These were the bathrooms for our whole section. All of us in our section had to use these bathrooms. So you can imagine when we needed to go to the bathroom we had to wait 20 to 30 minutes. We would go to the bathroom during lunch and then we’d only have 15 minutes to finish our food. That was one of the hardest things.”

As we exit Pyounghwa Market and cross toward Jeon Tae Il’s bridge, she motions across the main entrance towards the second floor. “Kookmin Bank was there. That’s where Jeon Tae Il doused himself with gasoline.” On the street below lies an inscription: “Here is the place where Chun Tae-Il shouted while his body burst into flames, ‘We are not machines. Abide by the Labor Laws!’ November 13, 1970.”

As we exit Pyounghwa Market and cross toward Jeon Tae Il’s bridge, she motions across the main entrance towards the second floor. “Kookmin Bank was there. That’s where Jeon Tae Il doused himself with gasoline.” On the street below lies an inscription: “Here is the place where Chun Tae-Il shouted while his body burst into flames, ‘We are not machines. Abide by the Labor Laws!’ November 13, 1970.”

We cross to the Jeon Tae Il bridge. She points at the brass inscriptions on the ground. “Mine is somewhere over there. We helped pay for this bridge with workers’ donations. Each brick cost 100,000 won.” As we stand in front of the statue of Jeon Tae Il, I ask, “What was Jeon Tae Il’s impact in your life?”

We cross to the Jeon Tae Il bridge. She points at the brass inscriptions on the ground. “Mine is somewhere over there. We helped pay for this bridge with workers’ donations. Each brick cost 100,000 won.” As we stand in front of the statue of Jeon Tae Il, I ask, “What was Jeon Tae Il’s impact in your life?”

“Whenever I was beaten up, or when I was suffering, I would think of him. ‘I am not dead like Jeon Tae Il.’ It put things into perspective, and it placed in us a sense of responsibility and guilt. After all, he had died for us.”

We finish our evening over grilled fish at “Restaurant of the Masses.” (Dongdaemun Market is known for its grilled fish.)

We finish our evening over grilled fish at “Restaurant of the Masses.” (Dongdaemun Market is known for its grilled fish.)

As she concludes our evening, I catch a glint in her eye, “Back when I was a textile worker here, I always wanted to eat at these grilled fish places, but I couldn’t afford it. Later, when I could afford it, I didn’t have the opportunity. Thanks to you, I get to eat grilled fish here for the first time and share my story.”

Lee Cheong Gak: “The Shit Water Baptism”

“I am the third daughter. My name means “bachelor.” It was so that I’d be the third and last daughter, and the next one would be a son. My father just drank at home, so my mother and sister worked, but even then we couldn’t manage three meals a day. When I was 18, I went to work for the first time. I worked in factories for 12 years until I was fired. “

“My sister went to work for Dongil first, then I went there. Dongil was bigger and better than other factories at that time. You could work in textile or lighter factories. Dongil was better than the lighter factory. It was really competitive getting a job there, so when I got hired, I was happy and proud. I could make money now and live like a human being, so I worked very hard. I was eighteen at the time. Dongil was a large factory so they had to obey the law. Still, people lied about their age using their sisters’ IDs, and the company just turned a blind eye.”

“We got paid by the piece, so we would try to work as much as possible. We would start at 8 a.m., eat lunch for 15 minutes, and then dinner at 10 p.m. Sometimes, when we had to meet a deadline, we would work 24 hours straight. The company ran three shifts: 5 a.m. to 2 p.m.; 2 p.m. to 10 p.m.; 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. You couldn’t eat when you worked, so you ate before and after. So people’s stomach would be ruined and because of the heat; we would develop athlete’s foot. To stay up, people would take stimulants.”

“There’s a song by Kim Min Ki about how when the boss’ dog gets sick, an ambulance takes it to the hospital while in the factories the workers toil away. Kim Min Ki went to work in the factories for a year to write that song. He wrote a song about a worker with six fingers. He received 50,000 won (about $50) for each of the four cut fingers, but because he was saddened, he drank it all away. At the end, not even the money was left.” Lee Cheong Gak starts to sing. There is no timidity in her voice, just emotion at singing the fighting songs of her youth. Cho Soon Young joins her. After the song ends, both laugh.

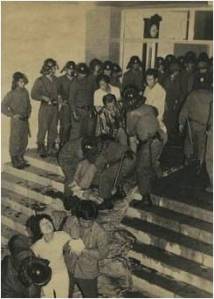

While 90% of its workforce was women, the leadership at the Dongil Union was dominated by pro-company men with little interest in the working conditions and wages of female workers. In 1972, women who had been involved in small group activities organized by the Urban Industrial Mission successfully organized to elect the first female president. Soon after, the company had male workers and the police to harass the women’s organizing efforts. In 1976, after male workers locked in the female delegates in their dormitories and elected a new male union president, the women staged a sit-in strike. On the third day, after the women resisted management’s efforts to draw them out by cutting the electricity and water, police were brought in to drag the women out. As they saw the police approaching, the women undressed thinking that “men cannot touch undressed women.” 500-800 naked women held each other tightly and sang union songs. In 1978, when an election was held for the union’s executive committee, pro-company male (and two female) workers splashed human excrement upon the women coming to vote. Its leaders, including Lee Cheong Gak, rushed with their stained clothes to a neighborhood studio to document the indignities they had suffered. It became the infamous “shit water baptism.” They would lose their struggle as the National Textile Union collaborated with the company to neutralize the women led union. Although 124 of its leaders were fired and blacklisted from taking jobs in other factories, their fierce fight inspired and fueled struggles such as the one at YH Trading Company.

We ask her what she thinks about the worker movement today.

“There is division among workers today – a division between regular and irregular workers. The workers of large corporations care only about their own wages. They need to support and struggle alongside the irregular workers also. Maybe the US and Northern Europe are different where there is not such a large gap between regular and irregular workers. But in Korea there is a big difference. Sometimes the regular workers negotiate contracts so that they can pass their regular worker job to their children. But the regular workers should be helping the irregular ones financially in their struggles. For example, in Incheon, there are two GM Daewoo factories a small and medium one. The KCTU has members in both the big corporations and the small and medium companies. However, when the workers in the small and medium enterprises wage a struggle, the ones in the big corporations don’t come out to support.”

Choi Soon Young: “Women Workers Brought Down Yushin”

“To understand Korean society you need to understand the Korean War and the industrialization that began at the end of 1960s. At that time we were a very different and poor country from the one we are now. Because our country was so poor, we sent people to Germany as workers and babies overseas for adoption. People had to come from the rural areas to the factories in order to make money. In Korean culture, they would send the son to school and the girls to the factories to help financially by working.”

“During that time Park Chung Hee made the lives of farmers very difficult. This was to create more workers and lower wages. During that time Korean workers, in particular women, were unskilled, so their advantage was their cheap labor. So, we see that during the 60s and 70s women were the majority of the workers in the large corporations. Back then Samsung and LG were clothing producers. During Park Chung Hee’s dictatorship Labor Standard Laws existed, but were not enforced. The worker’s union movement during the 70s was hard. The Christian groups, such as Christian Academy, did a lot. They worked to raise consciousness around religious reform, farmers, workers, and students. The idea was to train the leadership, and then when the leadership went back, they would educate others. At that time, the education that they received was considered radical and even shocking. Under Chun Doo Hwan we got red-baited. We would meet in small groups based on sectors, and learn theory through plays that we were one.”

YH Trading Company was a major exporter of wigs to the United States. It had been established with government financial support, yet, its managers were investing their profits in other companies. The major struggle against the YH Trading Company took place in 1979 when management announced that they would shut down the wig making plant, even after they had laid off half the workforce.

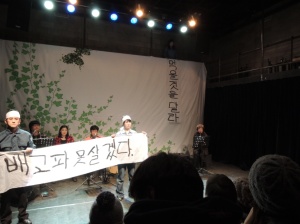

“During the end of the 1970s the repression against workers and farmers intensified, so the workers and farmers also started to intensify their protests. After we saw how they had broken Dongil Union, we decided that we would hold a last struggle regardless of whether we could win or not. We went to the New People’s Party building so that we could carry out a long term occupation struggle.”

On the third day of their occupation, a thousand police entered the building to remove the hundred or so workers. In the ensuing struggle, one of the union delegates, Kim Kyung Sook, was killed after falling from the fourth floor. The leader of the New People’s Party who had permitted the occupation was arrested.

“Because of that struggle lots of other workers also gained strength and inspiration. There were many other solidarity protests. The struggle at the New People’s Party exposed the Park Chung Hee dictatorship to the rest of the world. After that struggle Kim Yong Sam was incarcerated. This was a big deal because he was the leader of the opposition party. For someone of that stature to be incarcerated was a big deal. When Kim Yong Sam went on hunger strike, this got even bigger. The people in Busan and Masan protested because their representative had been locked away. Ultimately, it was an argument about how to deal with the Busan-Masan uprising within Park Chung Hee’s cabinet that led to Park Chung Hee’s assassination and the end of the Yushin Regime. So, the YH struggle sparked the series of events and protests that led to the fall of the Yushin Regime. Women workers brought down Yushin.”

Ripple Effect

This visit was part of the International Strategy Center’s Korean History, Economy, and Politics program. While the program centers on Korea’s social movement struggles and its protagonists, its purpose is to deepen participants’ understanding of Korean society and have them re-examine their relationship to it. As such, the participants are the other half of the program. Below are their thoughts:

“A month after watching the 70여공 play to commemorate March 8 Women’s Day, we met with the three former women garment factory workers whose stories were represented and retold in the performance. Hearing of their family backgrounds, how they came to work in the factories and their courageous struggles for a strong union and workers’ solidarity made the so-called ‘miracle’ of Korean industrialization come alive. I was inspired by the strong sense of unity, sisterhood and pride in their work that these women maintained, despite experiencing deep injustice from their workplace and their government. The personal oral histories have given me a much deeper understanding of who made the real sacrifice to make Korea what it is today, and why it is so important for women and workers to continue the struggle for representation in society.” – Ana Traynin

“Stepping back in time into a café with walls that have so much history was a unique experience. It was effective in connecting me to a past that I was not a part of. Touring the structure that once held the garment factories made the stories and history more tangible. It helped put the past into perspective. Listening to the three women talk about their lives and the struggles of the union was inspiring. Having the opportunity to ask questions in a more intimate setting gave us the chance to reflect on and clarify all the things we have learned so far. The dialogue the ISC is building between foreigners and Koreans is so important. It allows the stories and struggles of Koreans to reach and impact more people. The first step towards action is always education and dialogue.”– Erica Sweett

“This month’s meeting felt like a natural continuation of last month’s, when we watched the performance of ’70여공. At that time, I felt incredibly moved by the stories that each woman shared about her experience as a young factory worker and wanted to speak with them, but didn’t even know where to begin. This time, I knew far more about both the general history of Korea’s labor movement and each woman’s background, and was able not only to ask more meaningful questions but to better appreciate their answers. I had always thought of labor as being a male-oriented, male-dominated movement, but speaking with Shin Soon Ae, Lee Chung Gak, and Choi Soon Young opened my eyes to the central role women played in building Korea’s labor movement. Furthermore, many of them were in their early-mid twenties when they first joined the movement which, as a twenty-two-year old myself, I found incredible. I left at the end of the weekend feeling not only inspired by what they had shared, but with a sense of duty towards carrying on the spirit of their work in some way through my own.” – Stephanie Park

“Having the opportunity to meet and speak with these ladies was an incredibly humbling experience. The sacrifices they made and the passion they offered to their cause was -and continues to be- an inspiration to those who aspire to change their circumstances. I’ll never forget their stories, and I’ll carry their dedication with me into my future social justice work.” – Taryn Assaf