by A.T.

These days, most high-school-age Korean girls put on school uniforms and double over studying from morning to night, at the same rate as their male peers. As a visiting native English teacher in Korean high school, I’ve heard the word “hell” used more than once to describe these three years. However much they may hate it, for young people this remains the path to a kind of status denied to thousands of poor, rural girls growing up under Park Chung-hee’s military dicatorship of the 1960s and 1970s. Much of Korea’s economic progress, or the so-called “Miracle of the Han River” was carried out on the backs of workers like Shin Soon Ae of Cheongyye Union, Lee Cheong Gak at Dongil Textiles and Choi Soon Young at YH Trading Company.

As young women in the 1970s, Shin, Lee, Choi and their peers made up over 80% of the textile labor force. They sacrificed their youth, pouring into Seoul and Incheon to labor in factories and support their families. Instead of bending over textbooks, they spent their teens and early twenties bent over sewing machines in four-foot dusty attics. Sitting with these women in the quiet setting of Seoul cafes and hearing their stories from a distance of decades put a human face on cheap clothes and economic growth. It also revealed the deep-rooted context for the current labor repression under Park Geun Hye – the former Park’s first child and a woman roughly the same age as these three workers. The women’s personal histories make it clear who really made the sacrifice responsible for building Korea into a wealthy nation.

I’ve walked through Seoul’s huge Dongdaemun shopping district several times. I’ve bought clothes from one of the hundreds of small vendors. One warm summer night, as I walked outside after midnight, crowds and “Gangnam Style” were still jamming the streets. Dongdaemun’s late night shopping experience is one of Seoul’s prime tourist and fashion attractions but do any guides bother telling the history behind this after-hours cheap shopping party? Under the military curfew of Park Chung-hee’s industrialization regime, people were forbidden to be out in the street in the middle of the night. Instead, they stayed in the former bus terminal nearby and swarmed out at the break of dawn. Wholesale buyers and retailers from all over Korea would take the bus at 11 pm and arrive at Dongdaemun by 4 am just to get around the curfew. From this early bustling atmosphere, the late-night shopping mecca was born.

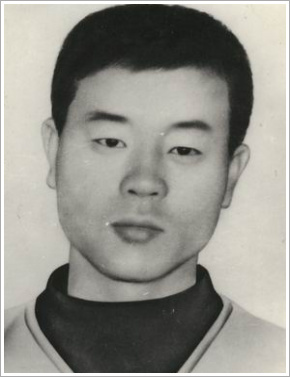

Just down the road from Dongdaemun’s shiny modern shopping malls, entering Pyeonghwa Market’s Myeongbo Dabang coffeeshop feels like stepping into another era. Usually, when I see the discreet “Dabang” signs, I assume these are just places for old men to hang out. I learned that back in the 1970s and 1980s, before the Starbucks, Caffe Benes, Tom n Toms and other chain coffee shops popped up all over Korea, places like Myeongbo served as prime meeting spots. Yet, as former Cheongyye Union worker Shin Soon Ae recalled with us over coffee, these same drinks were nearly off-limits for her and nearby workers, as they cost a full day’s labor. Myeongbo Dabang is where Jeon Tae-il held worker activist meetings before infamously setting himself on fire at the Pyeonghwa Market entrance on November 13, 1970. Knowing the prohibitive cost for workers, he bought drinks for everyone and made sure they could attend the meetings. Who knew that expensive coffee planted the seeds for Korea’s labor movement?

Shin, Lee, Choi and their sisters in the factories may have given up their formal education, but Jeon Tae-il’s sacrifice led to more than just the founding of the first workers’ union, the Cheonggye Union. It also led to the creation of a different kind of learning center – evening worker’s classes. Although, from day one, the unions had to fight merely to exist, through these classes they taught the female workers – who in the beginning didn’t know the meaning of a union – to organize and instilled in them a new sense of pride that couldn’t easily be taken away. Here, exhausted no-name laborers transformed into valued human beings who would eventually use their capacity to analyze and critique their situation to rise up against inhumane workplace conditions. While their peers in high schools and universities were busy learning facts, figures and national propaganda, these young women received education that made history, one that sowed the seeds of revolution that would lead to the end of Park Chung-hee’s rule.

Women struggling side-by-side also contributed to the ushering in of a concept that, according to Shin, the 1970s workers didn’t yet grasp – feminism. While burning in the streets of Seoul, Jeon Tae-il screamed “stop exploiting women!” Yet it was the women themselves who would fight this exploitation. Although they may not have viewed it this way, by organizing together with such strength and dignity, these women laid a strong foundation for the future of the Korean women’s rights movement. Lee Cheong Gak from Dongil Textiles recounted for us the shocking and unforgettable incident of being covered in human feces by male company thugs, simply for wanting to vote for a woman to lead their union. The response by Dongil’s female workers was equally unforgettable. By stripping half-naked, holding hands and forming a human wall against the riot police, they did something their male counterparts wouldn’t have the power to do. A single act set an irreversible precedent.

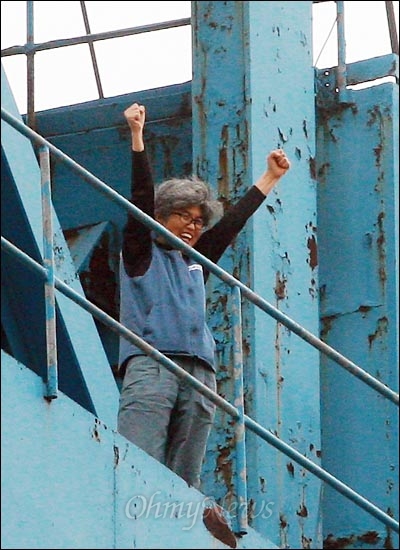

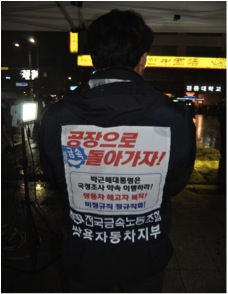

After Park Chung-hee’s assassination, Choi and Lee remember feeling a sense of elation. It didn’t last long, as the Chun Doo-hwan took power, companies busted worker-led unions, and members like Shin became jobless fugitives. Yet the 1980s saw the labor movement become infused with thousands of students, inspired by the previous decades’ struggles. Together, these powerful forces led the democratization movement that would transform Korean society.

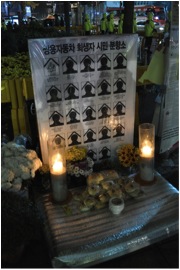

With the current tragic events regarding the sinking of the Sewol ferry leaving Korea awash in a wave of mourning, many questions arise. They are not new questions, but they now seem especially pertinent. Under a capitalist system, what is the worth of one human being? Workers, as well as dead bodies, are assigned numbers. With so much technological progress, where are we really going? Towards societies that overcome the unequal structures of the past – or ones that value speed and the bottom line over peoples’ safety and well-being? Since the 1980s, when Korean students joined the labor movement to organize for democratization, it seems that the country’s compass has swung in the other direction – towards complacency and a fight for status and success instead of freedom. Perhaps now that corruption and carelessness have been revealed in such an ugly way, these questions will again begin to spur collective action that inspires international movements, as Korean workers and activists have done in the past. Perhaps it’s time to reignite the spark.